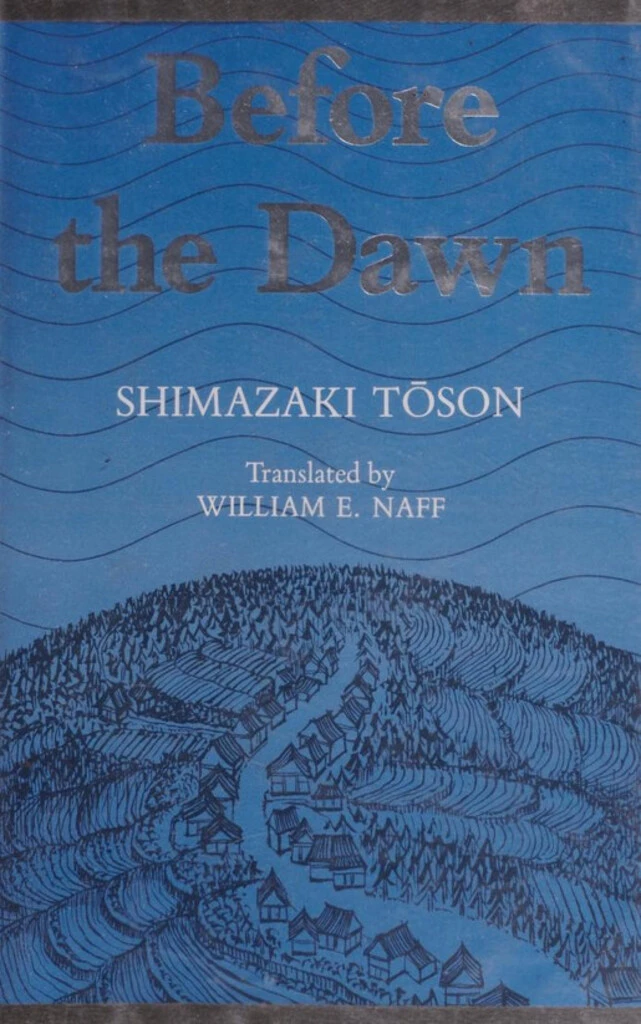

Context

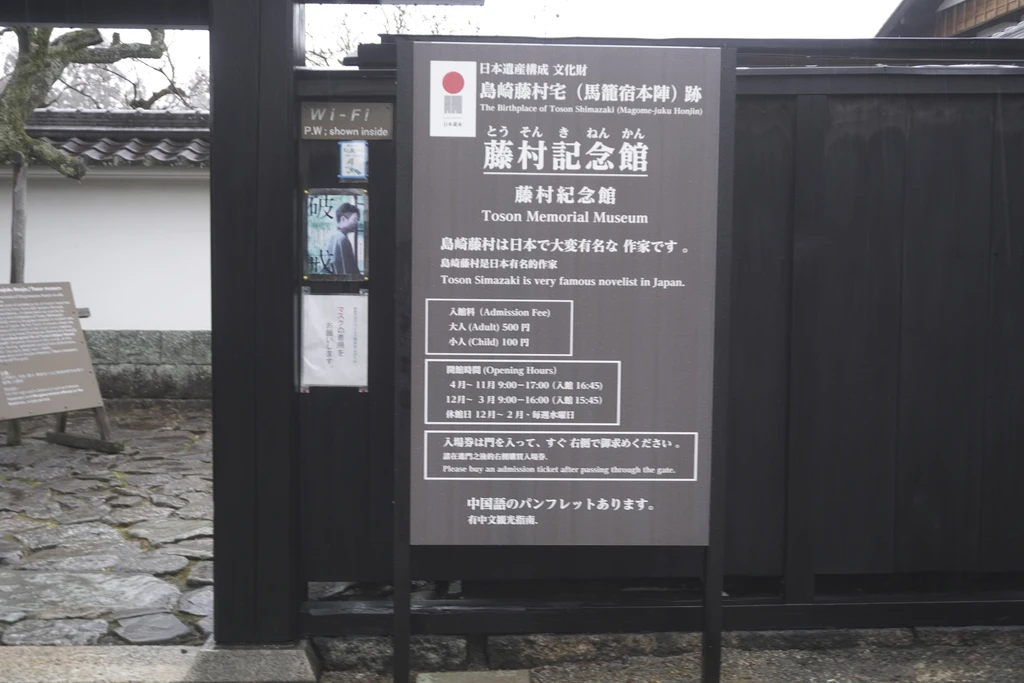

I’ve called this the Great Japanese Novel but it’s better described as creative non-fiction. Before the Dawn is the story of Aoyama Hanzō, who was an official responsible for the post station at Magome in the Miso Valley around the time of the Meiji Restoration. Magome was out in the boonies (mountain valleys) but also on the Nakasendō, a key inland route connecting Edo and Kyoto (the capital at the time). Part of the deal was that the shogunal regime aimed to prevent the subordinate lords—daimyo—from gathering too much power. How? By forcing them to invest in real estate. Daimyo had to maintain a residence in the capital where their families would stay (taken hostage, as it were), and also in their own domains. The daimyos thus had to travel along the Nakasendō regularly, and people had to do a lot of work to cater to their needs.

Hanzō is basically the author (Tōson)’s father. According to the translator’s notes, Tōson did a hell of a lot of historical research to write the book, and I can confirm that it is super heavy on historical context. I understand that the details are relatively accurate, but that the author had to reconstruct the information from archives, as Tōson didn’t know his father that well (see below for an anecdote).

This is not a thriller. It’s a brick. I did not want to bring it to Japan to read, because that was an extra kilogram of luggage to carry around. I did read it in Magome on my phone, via the Internet Archive.

I am the wrong person to explain the Meiji Restoration, but the tl;dr about that historical era in Japan was that the American Commodore Perry came with his Black Ships and forced Japan to open for trade with the world. Then the shogun (military leader) resigned and the emperor took back power. (Ask a historian for a better version). We see the effects of this major societal change throughout Japan, including in the cities and in the hinterlands.

The adventures of Hanzō

Hanzō is an idealistic disciple of the National Learning movement, which aimed to “restore the ways of antiquity”: as I understand it, the claim was that the shogunate, as well as Buddhism, had deformed the essential character of the Japanese people and Shinto-ism (whatever those are). This book is slightly the anti-“It’s a Wonderful Life”, and towards the end of the book, Hanzō reflects about how all his efforts brought no results, both at the national level (they were establishing the separation of church and state, rather than having Shinto as the national religion, which was something Hanzō worked on for a time; and talking about having a Parliament), and at a regional level (the locals were barred from using the local forest resources, e.g. cutting down the trees or practicing slash-and-burn agriculture, and hence in impossible economic situations). The book notes that he did teach many of the villagers to read, but also that he couldn’t get behind the new curriculum. In any case, to me, the author is aiming to show National Learning and his father’s pro-commoner beliefs in a positive light, even if he himself converted to Christianity.

An interesting moment late in the book is when Hanzō goes to Tokyo to visit his third and fourth sons; he’d sent them away to be educated. The fourth son, Wasuke, is the author. The text describes how the 12-year old author is so embarassed by the father’s provincial mannerisms. Teenagers! Even one and a half centuries ago and across cultures! Also Wasuke gets permission to learn English, although the translator’s notes mention that the book is written in challenging idiomatic Japanese appropriate for the action at hand. (I got confirmation that the original Japanese of the book is really quite hard to read in 2023 from Asako, who grew up in Japan).

Hanzō’s End

Hanzō does two major things that are Not Done. First, he throws a fan into the emperor’s carriage with a (pro-emperor) poem, and gets charged with endangering the Emperor but is eventually not significantly punished. Second, precipitating the end of his life, he attempts to burn down the local Buddhist temple. As a result, he gets locked up in a cage until his death (a few months later), by the villagers, who are very much afraid of arson in villages made of wood. Hanzō dies of beriberi, which is a Vitamin B1 deficiency; maybe that would have not happened if he had not been locked up.

Although the villagers think Hanzō is crazy, after Hanzō’s death, the local priest asks Hanzō’s disciples whether it was actually not an act of insanity, but rather an intentional anti-Buddhist (pro-Shinto?) act. Through his life, Hanzō had supported the temple, sort of, while removing his ancestors from the Buddhist burial plot; as with many human acts, understanding motivations is not straightforward. Even the author of the acts might not know.

Discussion

Sometimes we think that we’re only started talking about mental illness in the 2020s, but of course there have been madmen throughout history and in literature. This book is another perspective on a man who may or may not be mad; it’s up to the reader to decide about Hanzō.

The translator’s notes also say that one can read a lot into what is not said. I guess. Hard without a lot of context into Japanese culture, which I do not have. All I know is how to throw and pin people using Japanese techniques. (Kano Jigoro is also very very much a Meiji Restoration figure and judo is the thing done by the modern Meiji man, but neither judo nor Kano show up; an uncle-like figure is seen practicing his traditional archery.)

Links

- Internet Archive version of the book

- Washington Post review of the translation of Before the Dawn from 1987.