Table Of Contents

Turns out I picked up two books by this author at the library a few months ago; the seabirds book is much newer (so way more pictures) and focused on seabirds. There is a capsule review of that book in my July summary.

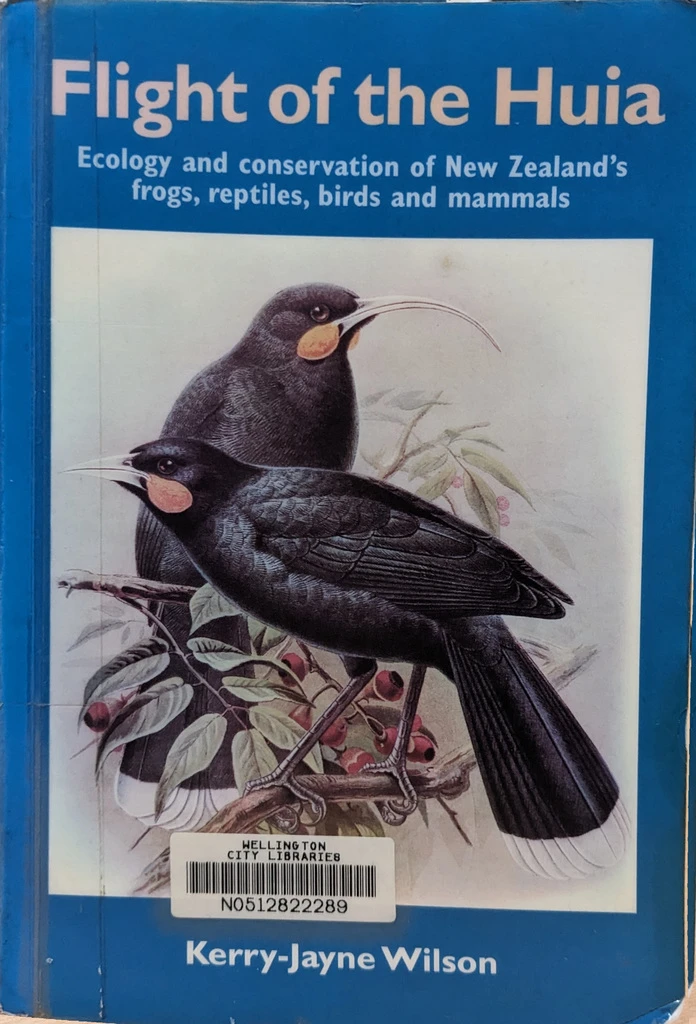

- Kerry-Jayne Wilson. Flight of the Huia. 2004.

This is an book that could serve as an undergraduate-level New Zealand ecology textbook (and it says so on the back). New Zealanders are pretty bird-focussed, but this book also talks about bats, reptiles, invertebrates, and plants, especially those that are endemic to New Zealand.

This book is from 2004, and it’s interesting to be able to look up “what happened next”. She writes: “I expect that in 20 years’ time the management methods described in this book will have been superseded by much more sophisticated and cost-effective controls”.

- From pest control to eradication: since 2004, the Predator Free 2050 project been approved (in 2016, though still somewhat aspirational), and actively being worked on. There is a detailed 5-year progress report from 2021. This moves from running-in-place (the book talks about how NZ hasn’t lost a vertebrate species in the last 40 years, though some species are on the edge) to something that is potentially more stable, should it succeed. You don’t have to keep dumping poison in the environment (and having it get less effective over time). Zero Invasive Predators on elimination.

- Predator Free Wellington, Zealandia, and Capital Kiwi have made huge strides, with kākā now being common (I hear them all the time and see them every other day) and kiwi being released in the hills not far from here. In the book: “on the mainland both [North Island and South Island] forms are now thinly distributed through a few large tracts of indigenous forest.” (Cover photo: hills near Wellington where kiwi have been released by Capital Kiwi).

- The concept of mainland islands was coming down the pipe. Zero Invasive Predators writes about Perth Valley, which is a eradication of predators over 12,000ha since 2019. Instead of fences and water, they use rivers and mountains.

About specific species:

- Wetapunga, the biggest insect in the world, were limited to Little Barrier Island and threatened by kiore. The year the book was published, the kiore were eradicated on Little Barrier Island, over the objection of some of the tangata whenua Ngatiwai. Wetapunga are now subject to a breeding program run by Butterfly Creek and the Auckland zoo, producing 4000 creatures, and they have been released to an additional 3 islands.

- There was a theory that kiore (Polynesian rats) had been in New Zealand for 2000 years, but it was actually found to be faulty data. They came with the Māori.

- Black stilts/kakī are still with us but they seem to be treading water for now ("generally upward trend" per DOC Kakī Recovery Programme lead), with lots of breeding and releases but not so much survival; they are up from 23 adults in the 1980s to 156 now, but they also release about 150 per year. Habitat loss in the braided rivers continues to be an issue.

- Fairy terns are also just barely hanging on.

At a higher level:

- New Zealand is really a world leader in species conservation and has a lot of diversity in birds that doesn’t exist elsewhere. Instead of cows, we have takahē (now 70 years from re-discovery). It’s hard to digest grass!

- Alberta has no rats but winter is a big advantage there. The rats will freeze to death on the Prairies if they don’t have anywhere to shelter from the cold.

- Practical vs theory-based approach. The work with saving species has been carried out by the Wildlife Service and later the Department of Conservation, who were very practical-minded, as opposed to more theory-based conservation work in North America. Makes me think of some of what Amy Ko has written about theory in computer science, specifically human-computer interaction. The NZ approach tends to resonate with me; I’m more concrete than many other academics.

- Species versus ecosystems. The author points out that we’ve often focussed on particular bird species (charismatic megafauna, in someone else’s words). That’s OK if it’s an indicator species, but could also be a bad metric. It is, however, easier to measure than ecosystem health. I also think the now broadly-understood notion of “ecosystem services” postdates this book.

- Local extinction versus global extinction. We worry about global extinction of a species, but that happens after all the populations are wiped out.

- The author also does some analysis to figure out which of the predators killed which of the species. This is sometimes important but I guess New Zealand these days aspires to eliminate all of rats, stoats, and possums, so maybe it doesn’t matter so much. Cats, though, aren’t talked about as much. The infamous Stephens Island lighthouse keeper cat killed the last Stephens Island wrens, but the author points out that they were already driven to extinction elsewhere, not by cats.

Interesting facts that I didn’t know:

- species from Australia failed to establish in New Zealand because the landscape was so different, at least until the Europeans started modifying the landscape to make it more similar to everywhere else; indeed, most introductions fail, though of course rats, stoats, and possums did not.

- two notes about birds that formed male/male pairs, in one case until young females became available (and then they paired with the young females).

- NZ reptiles basically don’t go anywhere: if you release them they are going to stay basically there. Makes it easy to re-find them I guess.

- Matiu/Somes Island has a unique species of tuatara (which we did not spot when we were just there last weekend.)

- section heading: “Possums, the all-round bad guys.”

- muttonbirding (harvest of newly-fledged sooty shearwater/tītī) is allowed by the Deed of Cession of the relevant land and sustainable because most of the fledglings don’t survive anyway.

- the rule of thumb of 50 short-term and 500-long term individuals for a viable population (vs inbreeding) doesn’t seem to be well-supported by evidence; we don’t quite know why kākāpō are so hopeless at living (is it inbreeding?)

Great quote:

- “Jared Diamond likens a winged rail on a predator-free island to a backpacker placing 15 kilograms of bricks in her pack then tramping on half-rations.”

The 20kg of gear I was carrying the other day felt heavy.

Most of the book aims to be scientific and to analyze root causes from an ecologist’s perspective. She does provide a call to action in the final chapter. “Our biota is part of humanity’s global heritage”.