Table Of Contents

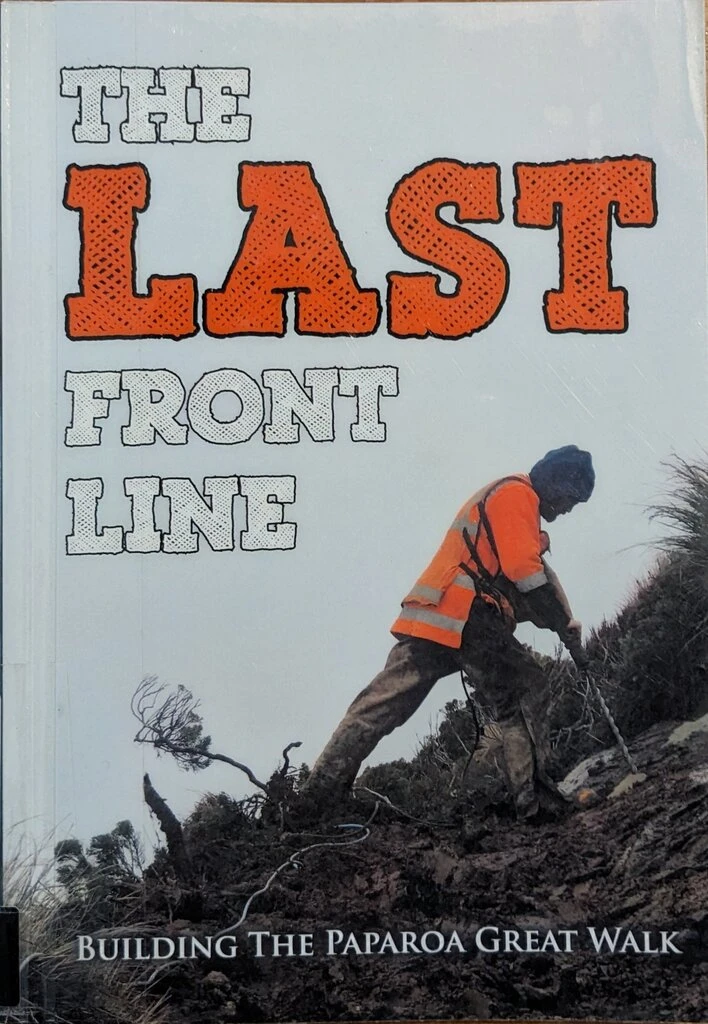

- Brendan O’Dwyer. The Last Front Line: Building the Paparoa Great Walk. 2020.

I saw this book when we were hiking the Paparoa Great Walk in September 2021; someone had left a copy at the Pororari Hut. It looked interesting but I didn’t have time to read it all, since I still had another day of hiking to go. Fortunately, the Wellington City Libraries has a copy in the system which I checked out (part of a haul of 7 books which I’ve finally worked through). The front lines in the book refer to the front lines of track construction (as represented by diggers); track construction was largely over when the last two diggers met.

About the Paparoa Great Walk

The Paparoa is a 55km track built for walking and cycling. It was commissioned by the government after the Pike 29 coal mining disaster and aims to develop West Coast tourism as well as serving as a memorial to the mining disaster victims, especially the Pike29 spur (to open in February 2024) leading to the memorial facilities on-site.

There’s the saying that things from before one is born have always existed, while things from after one is an adult are strange and new. Being in a different country, everything in NZ before my arrival always existed. So I didn’t realize that the Pike River Mine disaster was just in 2010 (not that long ago), with the Paparoa track being completed in December 2019, barely before we hiked it in 2021. It kind of surprises me that such a disaster could happen in New Zealand in 2010, but also not, in a country which had the White Island eruption in 2019 when there were tourists on the island, and also where there was a lot of neoliberal influence in the past (and, sigh, maybe the future).

Summary

The author, Brendan O’Dwyer (and not Brendon O’Dwyer, a different Irish emigré in NZ), signed up to help build the Paparoa Great Walk, and got quite invested in the mission. This is a memoir of his experience building the walk.

About the author

O’Dwyer grew up rural working class in Ireland in the 1980s. Maybe he is one or two years younger than me, but still an X-ennial. But, rural Ireland was very different from Montreal. Even though Montreal had and has less money than Toronto, it’s not Ireland-scale, and it is a city. O’Dwyer’s father built things with his hands. The author, on the other hand, was into computers as a kid and studied graphic design. And yet.

After arriving in New Zealand in his 20s, he describes trying all kinds of white-collar and blue-collar work, and concluded that he finds building physical things much more rewarding. (Me, I dabble in building things occasionally, but I definitely don’t do it professionally; I try to have some minimal competence at least.)

Joining the project

When he heard about the Paparoa Great Walk project, he signed up to work on it, as a way to build a lasting legacy in the part of NZ that he loves. He was keen: told that he’d need a bunch of certifications, he enrolled right away and got hired for the team. Though he had experience working with his hands, he didn’t have as much experience working with machines, and in the early days, he found that he was putting too much muscle into his movements as opposed to using the motor. Technique is always important (as in judo), but when doing things manually, muscle power matters.

On the job

The main conflict in this book, such as it is, is man vs wild. Specifically the weather, which can get really wild. (On our trip, we only experienced some rain in September—early spring). It’s not high enough to be snowy, but it will get windy and rainy, and the rain in particular can trigger slips and treefall. The teams had modern technology, so it’s not like the rock was going to stop their progress (it yields to explosives), but things can and did slip down the slope. A couple of times, diggers went down the slope, including one incident where the author was out for a couple of weeks due to a broken elbow.

Most of the time there wasn’t interpersonal conflict: the men were responsible and worked well as a team. There was one city boy, nicknamed Tenzing by the crew, who had some trouble adjusting to the mindset and physical labour required. I guess there should be a line between doing what’s expected, and overwork/burnout. I don’t know. When do you call in sick/tired? (Working out in the bush, you are less likely to bring in a cold.) There was also one early worker (O’Dwyer looked up to him) who, despite being quite experienced and capable, couldn’t take it anymore and quit.

I said “the men”, and the track crew was all men. The only woman that I remember being mentioned is O’Dwyer’s mountain-biking friend at the end who accompanies him when he tries out the track (on his beater mountain-bike) just before it opens.

Jobsite logistics

The workers did one- or two-week rotations onto the jobsite, usually getting flown in by helicopter to their camps. The camps sounded reasonably comfortable, though still rustic, and the generator was noisy. O’Dwyer particularly enjoyed their time at the Pororari Hut. (They are putting up contractors who are fixing up the track in 2023 in the emergency shelter on the track; I was wondering why it had a power outlet.) They did have to cook their own food (communally), though they did not have to hike it in. At one point, they got their hopes up about some sausage rolls etc from survivor families being flown in, but the rolls arrived at a different camp, alas.

A logistic problem with building a track is that you have to get back to the trailhead every day, which may involve an hour’s walk, and not with lightweight hiking gear! They did use motorcycles sometimes. But it wasn’t always a good idea, especially when there were slips along the way that needed to be fixed. O’Dwyer, incidentally, learned how to drive a motorcycle just for the job, and just started riding it in the bush, which is perhaps the most dangerous place to ride a motorcycle.

Philosophy / Sausage-Making in Trail Construction

Using a tramping/cycling path is mostly low-impact. The poop gets flown out by helicopter occasionally. But, building the track involves explosives, heavy machinery, and lots of hydrocarbons. (We’re not using pickaxes anymore, and even that would involve feeding the labour, which still involves hydrocarbons). It’s a high-impact change to the landscape. (In North America, we’ve also seen how e.g. wolves change the landscape, but I don’t think we know how birds change the landscape in NZ, except for theories about moa and lancewood/horoeka and heteroblasty). The track builders were hired to minimize visible impacts and to make things look natural by moving plants around and such, but O’Dwyer did think about the impact they were having, and decided that he was OK with it.

The Department of Conservation doesn’t seem to have the capacity to build the track itself, but contracted to, for instance, WestReef, which is a (Buller District) Council controlled trading organisation. Charitably: maybe it makes sense to have people familiar with local conditions do this, rather than a national organization? I guess it’s not private equity.

Current Status

It’s popular: not quite as popular as the Milford Track, but more than some of the more obscure Great Walks. DOC reported 6620 bednights in the 2021/2022 season. When you think about it, these tracks can’t really accommodate that many people: a hut has a capacity of less than 40 per day.

There is ongoing maintenance. “Contractors are working on the zig zag section leading down from the escarpment on the Paparoa Track Great Walk. Last reviewed on 11 September 2023.” All tracks require it, especially in geologically active regions, but also where bridges get flooded away (e.g. Heaphy Track was not open to through-walking last year due to a missing bridge due to Cyclone Dovi).

The Paparoa is a great track. I recommend it. Great views. The book is an easy read as well. The author’s mission was to tell some of the stories in the track’s building, and he has done so, adding a few pictures from the trac.

(By the way, many pictures in this post and on my site are clickable and take you to the gallery.)