Table Of Contents

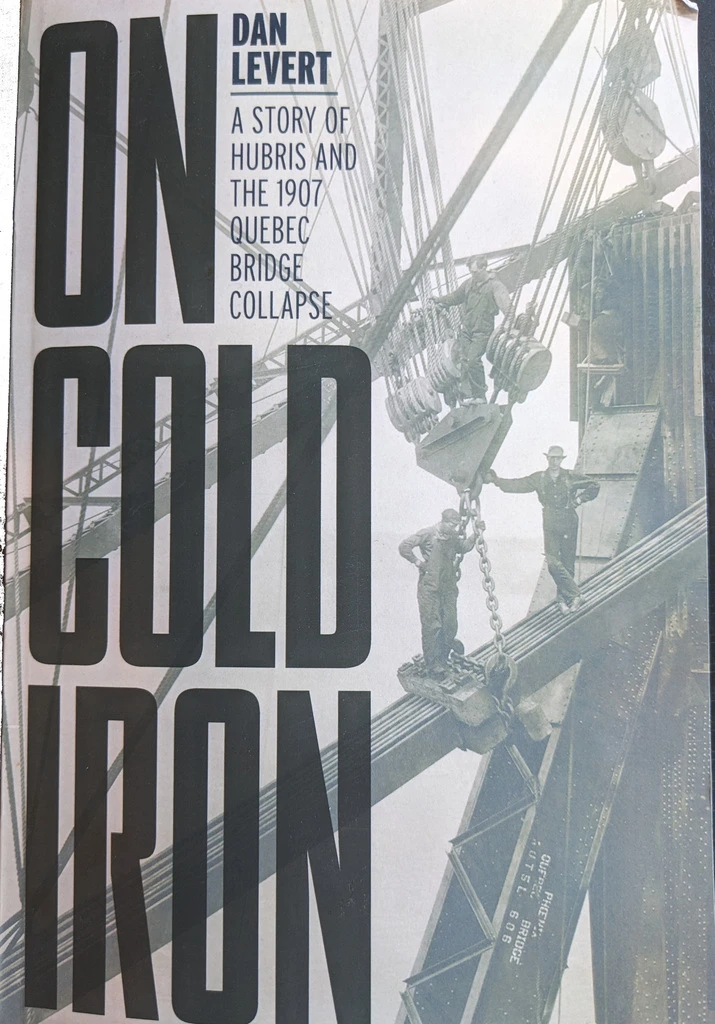

- Dan Levert. On Cold Iron: A story of hubris and the 1907 Quebec Bridge Collapse. 2020.

The Quebec Bridge disaster is a well known Canadian engineering disaster. Apocryphally, but not in reality, the iron from the Iron Ring that Canadian engineering graduates receive upon taking their Obligation came from the wreckage of that bridge.

Dan Levert, past president of Engineers Canada and a construction lawyer, recently wrote a book about the disaster and also the Iron Ring Ceremony; looks like it was a pre-pandemic retirement project of his, published in 2021.

I am a professional engineer, but not that kind of engineer. I am comfortable with expressing a professional opinion that there’s something wrong with the bridge in the picture above. That’s about as far as I will go.

The Ritual of the Calling of an Engineer

The book starts with “This book tells two stories”. The first story, accounting for 2 chapters, is about the Ritual of the Calling of an Engineer, as written by Rudyard Kipling upon request by Prof. H.E.T. Haultain of the University of Toronto. The idea is to impress upon engineering graduates their responsibility to society to, for instance, not design bridges that will fail. These days it’s not just bridges. Especially in my line of work, there’s the whole fall-of-democracy thing that tech may help with. Yes, I’m looking at social media and misinformation.

Since I have a Bachelor of Science degree in math and computer science, my path was to apply for licensure from Professional Engineers Ontario as a PEng, and then I went to the local Camp and asked to take the Obligation as a senior candidate. It’s a bit weird to talk about one’s equals and betters among the students that one has just taught, as mentioned in the Obligation. Also I suspect that part wouldn’t fly in New Zealand, which is perhaps more egalitarian.

Now, about Kipling. My early exposure to his work was through the Jungle Book, though I haven’t read it in years. Levert points out that Kipling was a huge fan of engineering and of engineers, though he didn’t have technical knowledge himself. So, in some ways, an appropriate author for the Ritual for 1922.

But now it is 2024. It turns out that not all of our graduates today are Christian white men. Indeed, in Software Engineering at Waterloo, the vast majority aren’t. Part of the controversy about Kipling was about his poem The White Man’s Burden; the most positive interpretation is that it is a call for the US to take up its share of responsibility to “civilize” the nations of the world (in particular, the Philippines) according to Western standards, even though this responsibility will cost it dearly. Less positive interpretations are that Kipling put white Western civilization at the pinnacle and is wilfully blind to the questions of exploitation.

In the context of the Ritual, one can certainly say that the 1922 text is hard to understand for the engineering graduates of 2024, though the sentiments of the core Obligation still hold, in my opinion.

The Bridge

Quebec City is located on the north shore of the Fleuve St. Laurent (or St. Lawrence River) “where the river narrows”. Lévis is on the south shore. The trans-Canadian train line at the time ran to the south shore. There needed to be a bridge, but the river is still wide enough that a cantilever bridge over the St. Laurent would be the longest bridge constructed to date, in 1907. Definitely pushing the state-of-the-art of the time. Tragically, the bridge failed during construction, causing the death of seventy-five men, including 33 from the Mohawk village of Kahnawake. Why did it fail?

The book describes the design and construction of the bridge, as well as the subsequent coroner’s inquest and Royal Commission. As I wrote above, I’m not that kind of engineer. The book comes with a glossary and some pictures, but there is a lot of discussion of compression chords (which failed here), and a picture of a truss like the one in the civilengineeringbible would have helped me.

What I can understand, though, is engineering management, supervision, and inspection.

Engineering responsibility

First, who was in charge? Essentially, Theodore Cooper of New York City was consulting engineer and had final say, and the Phoenix Bridge Company got the construction contract, but they didn’t really have qualified bridge engineers on site. (They did have a chief engineer who had no experience with bridges and deferred to Cooper).

Cooper tried to supervise the result from afar, with Princeton 1904 civil engineering grad Norman McLure as his chief inspector. Phoenix also had its own experienced inspector, Robert Kinloch, as well as Arthur Birks, an inexperienced MIT graduate, as their resident engineer of erection. In general, accountability was unclear.

Professional Engineers Ontario wrote about remote supervision of site reviews and emphasized that someone should really be looking at the artifact, even in 2020, though due to COVID, it might be not a licensed engineer. In 1907 there was no Zoom. Just before the failure, McLure travelled from Quebec to New York to check with Cooper, but there was no clear stop-work order from Cooper to the site.

Design issues

As I wrote above, the bridge pushed the state-of-the-art. Sometimes we talk about the ancient cathedrals that are still standing. We don’t talk about the ones that fell down while they were being built, or shortly thereafter. There’s survivorship bias.

In this case, Cooper was recognized as an expert in bridge design. So much so that his design was not peer-reviewed; a colleague was discussing some proposed change with Cooper, who replied “There is nobody competent to criticize us”.

Furthermore, in retrospect, he didn’t know what he didn’t know. In particular, the bottom compression chords were not strong enough and not tested. They did test some parts of the bridge but didn’t quite have the machinery to test these chords (until after the fact, where the construction company replicated the failure at one-third scale). They just didn’t think about the chords, apparently.

There was also perhaps an implementation issue, in that one of the chords (A9L) had earlier been dropped. It sounds to me like it would have failed ayway.

Collapse

Just before the collapse, there was some concern from the workers, foremen, and engineers on site: there was more deflection in the chords than there was supposed to be. Beams weren’t lining up. They didn’t really think the bridge would fall down, which is why dozens of men were on the bridge when it did. As I wrote above, McLure had gone to visit Cooper (though Quebec City is not right next door to New York City) and Cooper had wired the message “Add no more load […]” to the construction firm’s on-site office, but the message didn’t get read. Then the under-construction bridge collapsed and took down the workers with it.

The general concerns were, as always, time and budget pressures; it would have been undesirable to pause the construction, because all the workers might leave.

Another phenomenon that often happens, related to the normalization of deviance, occurred here. Engineer Birks seemed to be trying to convince himself that the observed deflections were nothing to be concerned about, because the load was well under the design load; instead, he believed that the deflections had been there all along. Ultimately, that didn’t go well for him, as he was on the bridge when it failed, and did not survive.

Reviews

Following the collapse, there was a coroner’s inquest (which could have found criminal liability, but didn’t), and a Royal Commission. I tell my students that they never want their work to be the subject of a Royal Commission: something has gone badly wrong if that is the case.

The inquest started first, paused when the Royal Commission started, and restarted before the Royal Commission finished (for unclear reasons). It took testimony, but was not expert, and found itself “unable to determine the cause or causes of the collapse of the bridge, but [felt] that it [was] our duty to declare that, based on the evidence heard during the inquest, all precautions were taken to ensure the construction of the bridge without danger”. (Of course, fall protection wasn’t required until many decades later, but standards in society change.)

The Royal Commission included three engineers; the chair of the Commission, Holgate, was an engineer in industry; the other members included the chair of the engineering department at the University of Toronto and an engineer who had recently left the faculty at McGill.

With the advantage of retrospect, Levert identifies a number of threads that the inquiry and the commission had raised but then failed to follow up on. There was a lot going on at the time and probably insufficient clerical support.

Holgate, the Commission chair, had wanted to talk more about the social organization of the bridge construction, but the other members wanted to focus on the technical aspects. They found that the bridge failed due to errors in design by Cooper and the bridge company engineer Szlapka, but not because of “lack of common professional knowledge, […] neglect of duty, or […] desire to economize”; it was because the state of knowledge was insufficient.

Note about the waterfall methodology

If you’ve been around software engineering for a while, you’ll have heard of the waterfall process (which was never intended to be a real thing). Even in the most engineering-y of engineering disciplines:

Bridge design is an iterative process.

although, to be fair, the iteration has more to do with estimating the load that the bridge has to support, while keeping in mind that the bridge has to support its own weight. I understand that client requirements for a bridge are way easier to characterize than client requirements for software.

The Phoenix Bridge Company did, however, de-parallelize its subsequent projects, making sure that the design was complete before starting to manufacture beams. Things do take longer to build today, partly because safety expectations are higher.

Pike River Disaster, New Zealand, 2010

And yet! 103 years after an engineering design failure killed seventy-five men in Quebec, there was an explosion at the Pike River mine which killed 29 men. I know as little about mining engineering as I know about bridge engineering, so it’s not for me to write about the technical failures, but it looks like cost and time pressures struck again, as well as design not suited to the NZ geological conditions (the ground is a lot more fractured than in Australia, where the CEO Peter Whittall was from. There was also talk of an inadequate mine inspection regime in New Zealand and bad design for the ventilation system which would vent the methane (“adequate ventilation is critical to the safe running of a coal mine” per the NZHistory article).

The Paparoa Great Walk and the Pike29 Memorial Track are part of the legacy of this disaster; the Pike29 Memorial Track is opening right now, in summer 2024.

Just as in the Quebec Bridge disaster, no one was found to be criminally responsible, though we really cannot say that the technical knowledge does not exist today. The bankrupt company was found civilly responsible, and in both the mine and the bridge, there was compensation paid to the victims’ families (through insurance in the Pike River case).

Furthermore, in New Zealand, the Supreme Court found that there was “an unlawful bargain to stifle prosecution”, and John Campbell recently wrote about those who are still trying to figure out how this happened. So, in New Zealand, there was the equivalent of no inquest, but there was a Royal Commission.

Conclusions

First, about money. Then, summing up.

Money

Two things: engineer pay and cost pressures on the project.

About engineer pay, the Obligation which goes with the iron ring includes the phrase “My fair wages for that work I will openly take”. Yes! We are doing work and taking responsibility, and we don’t do it for free.

Cooper wanted to charge $7,500 per year in 1903 dollars, but saw that the Quebec Bridge Company had no money, and agreed to $4,000 per year ($4,000 in 1914 dollars is $103,803 in 2023 dollars), which had to cover him, his assistant, and office costs. He said it wasn’t enough. Is it? I really don’t know how much effort he put into it. Let’s say he was on 4 projects and his portion of the fee was $60k. That’s an annual income of $240k, which is probably less than the world’s foremost bridge designer should be making.

Cooper did want to withdraw from the project; he was intellectually engaged but unable to visit the actual structure. But he was talked out of withdrawing. Probably he should have withdrawn. But that’s easy for me to say.

Overall

Engineering disasters share many common features: both technical challenges and social ones (i.e. time and budget pressures). We see them both in Quebec and Pike River. Lives were lost, money was paid out, reputations were damaged, but no one was put in jail. What to do when one is in charge of an engineering disaster? It is possible to quit or to whistleblow, but it’s not easy. I hope that no reader of this is going to have to wrestle with such a question in real life, or if they do, that they take the right decision. It really is a no-win situation.

References

- ACSE Technical Council on Forensic Engineering. The Collapse of the Quebec Bridge, 1907.

- Simon Nathan for NZ Ministry of Culture and Heritage. Pike River Mine Disaster.

- John Campbell. Why the Pike River Tragedy won’t be laid to rest. 1news.

- Royal Commission on the Pike River Coal Mine Tragedy. Report. October 2012.

- Royal Commission on Collapse of Quebec Bridge. Report on Design of Quebec Bridge.