Alison Ballance is a prolific author and former host of Our Changing World on RNZ, which is like CBC’s Quirks and Quarks but more nature-focussed. This book is about takahē, a flightless rail re-discovered about 75 years ago, formerly nationally critical, but recovering, due to heroic efforts by New Zealanders.

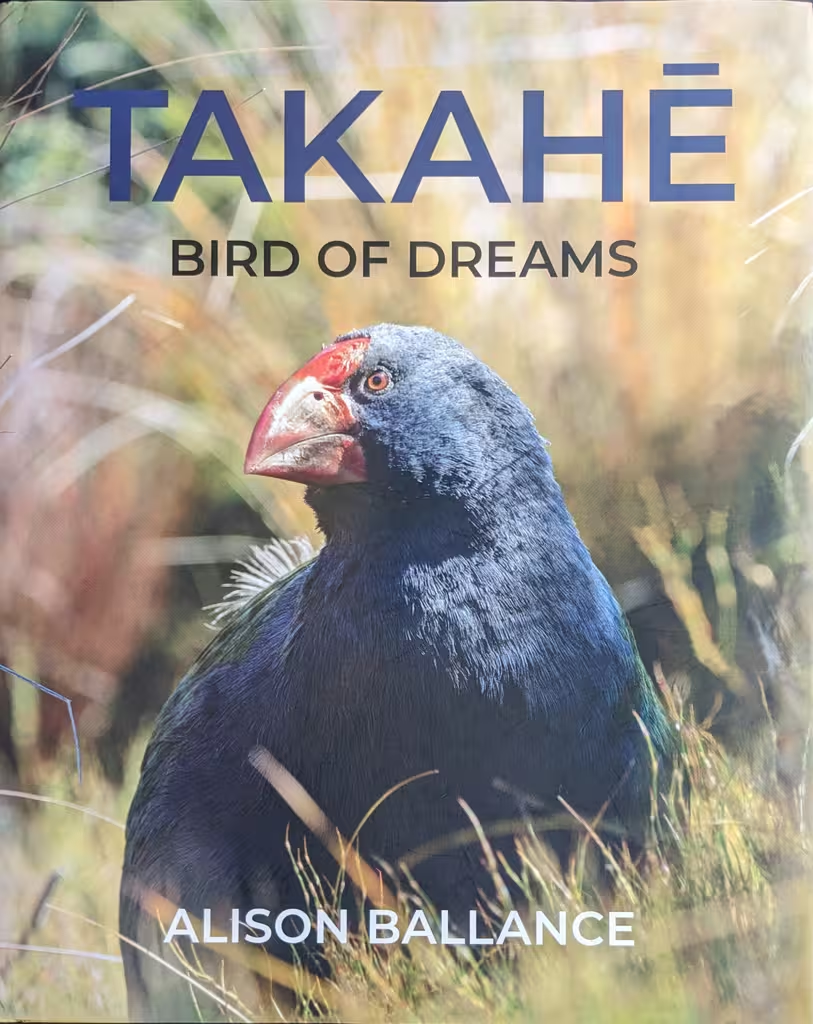

- Alison Ballance, Takahē: Bird of Dreams, Potton & Burton, 2023.

We were hiking on the Heaphy Track [pics] back in 2020 (our first Great Walk) and it was raining on us as we walked through Gouland Downs. To avoid hypothermia, we walked right past the Saxon Hut and slowly warmed up when we got to Mackay Hut. We then found out that a previous group had left a fire going and that there were takahē hanging out around there. Oops. Better luck next time.

I have seen these birds at Zealandia and Orokonui, but that isn’t quite out there in the wild. (A segment on one of the Air New Zealand safety videos has kids that are meant to look like Scouts saying “Takahē! In the wild!”).

I think the story of the takahē’s rediscovery by “Doc” Geoffrey Orbell (an actual doctor, i.e. an ear, eye, nose and throat specialist) is pretty widely known by NZ bird fans. He had seen a picture of the bird as a kid, heard stories of sightings, and worked out probable takahē habitat in the Murchison Mountains near Te Anau. As a hunter he was often out there and managed to find them in 1948, which made news around the world. I’d heard an interview by Ballance with Joan Watson, who was on that expedition. The last known habitat was not exactly easy to get to, which surely helped with the birds not getting eaten by predators.

The book is a solid coffee-table artifact. It’s heavy, hardcover, printed on thick glossy paper with full-colour photographs. Which is what you’d expect for a book where the visual element is important.

The bird is also a pretty heavy non-flying rail. It’s pretty colourful with a prominent red beak and yet it somehow disappears into the tussock (Ballance has a sentence mentioning its magical disappearing act).

There are four roughly chronological sections with the history of takahē conservation, from rediscovery through to the present. Each section is divided into a number of nuggets, each of a couple of pages and covering one topic. Good for those with a limited attention span or limited time: no need to read the whole book at once. We learn lots of interesting facts about takahē.

The takahē project is one of the longest-term projects to save critically endangered species in the world, and the book documents the history of this project from the beginning, when we didn’t know much. Technology (helicopters, radio transmitters, genetic sequencing) and scientific knowledge about these birds are really helpful. Deer and predators are really unhelpful, and the birds also occasionally drown or get into fights.

The four comparisons in New Zealand that I can think of include the Chatham Islands black robin (doing much better after dropping to a low of 5 birds), the black stilt (still just hanging on despite breeding every year), and the kākāpo and takahē (intensive management, slowly growing numbers).

One fact which I’d known about, but which is detailed more in the book, is that it is possible to hand-rear takahē, but then they have lower reproductive success than takahē who are taught what they need to know by older takahē. So they don’t hand-rear anymore.

Apparently if you coop up two takahē, they will breed, but then if you let them out in the wild, they may divorce. Takahē divorce also happens in the wild sometimes too. But for the purpose of maximizing genetic diversity, the takahē project chooses mates carefully. Some pairs, and some birds, are more prolific than others.

The current state of takahē is that we are close to having 500 birds, all in New Zealand, and running out of places to put them. Unlike kākāpo, there are two wild takahē populations, in the Murchison Mountains (where they were first rediscovered), and in Goulard Downs (which seems like not the best place for them to breed; there’s a discussion of that in the book). The vast majority of kākāpo are on predator-free islands. It is possible to view retired takahē, but generally not kākāpo, unless that species’ spokesbird Sirocco is on tour (rare, hasn’t happened for a while).