This is a book report summarizing a book that summarizes 11 trips over, across, and around Aotearoa. While I was borrowing How Infrastructure Works, I came across this book and thought I’d check it out as well. I’m aiming to return it to the library tomorrow, so let’s get some thoughts out about it now. Definitely this book was a quicker read than How Infrastructure Works, which was dense with ideas and technology.

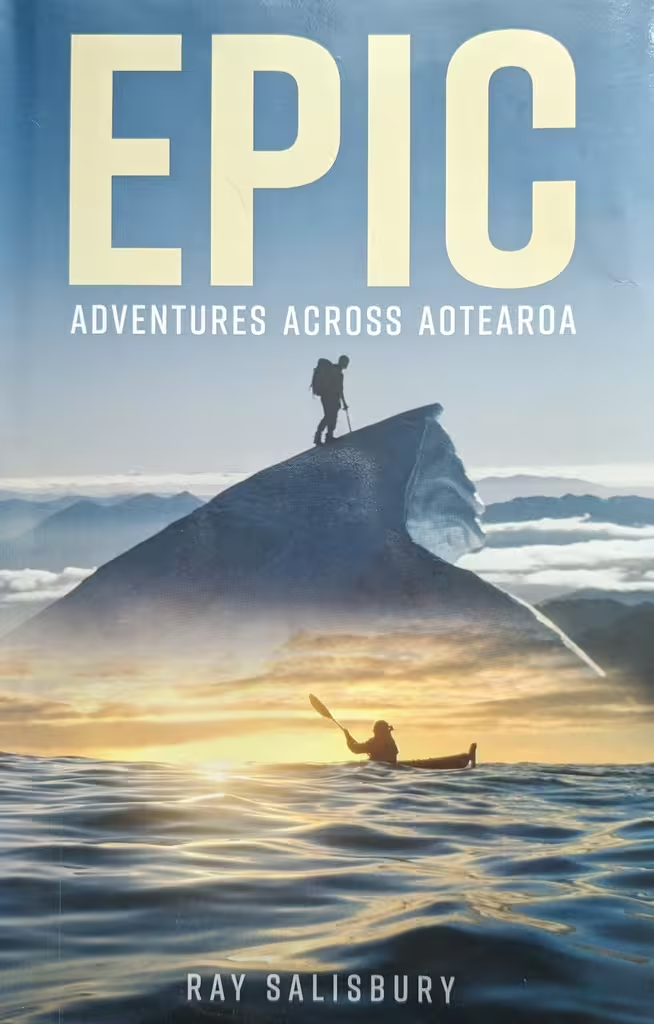

- Ray Salisbury, Epic: Adventures Across Aotearoa, Exisle Publishing, 2023.

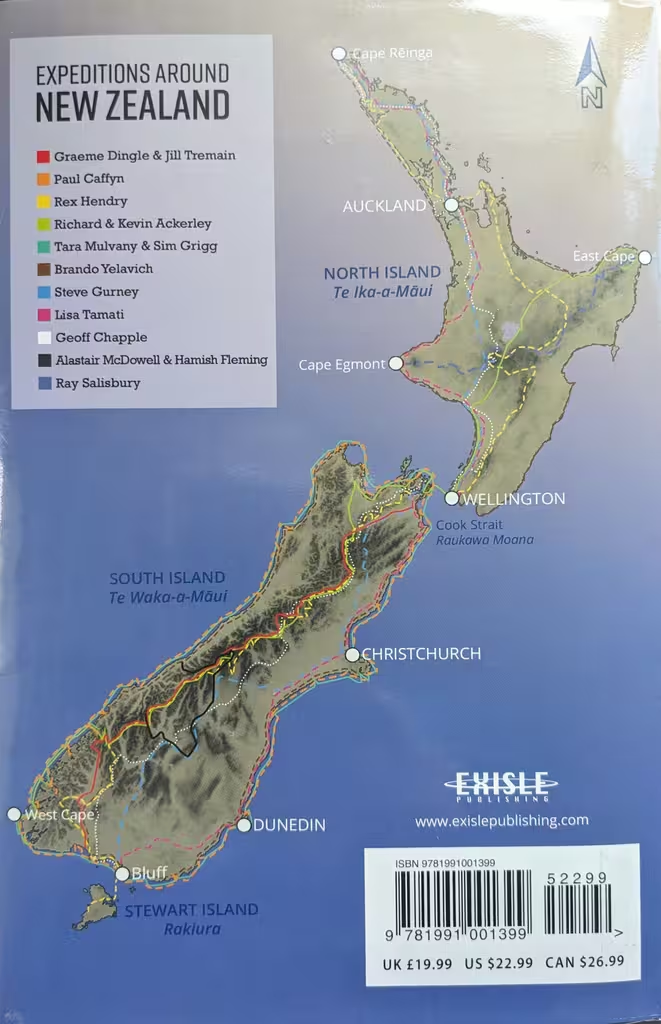

New Zealand is approximately about the same size as the United Kingdom, but the mountains are bigger. Dozens of parties have completed traverses across the mountains, further dozens have paddled around the islands, and thousands of trampers now set out to thru-hike the Te Araroa Trail each year. Ray Salisbury retells the stories of 11 significant traverses or circumnavigations.

The book starts with the Southern Alps traverse by Graeme Dingle and Jill Tremain, back in 1971, and described in Dingle’s book Two Against the Alps. I understand it’s a classic in the genre, and would be hard to pass over.

It continues with a mix of circumnavigations and alpine traverses of various kinds, from Dingle and Tremain, through to the single-push ascent of the 24 3000m NZ peaks in 2021. Sometimes they are fully-supported races, like the 1990 run-bike-kayak Xerox Challenge. Other times, they are paddles with large solo components, as in Paul Caffyn’s first kayak circumnavigation and Tara Mulveney’s first winter circumnavigation. Lisa Tamati’s run is reminiscent of Terry Fox’s Canadian run, although New Zealand is smaller, she didn’t have cancer, and she finished her run. The book also includes information on what the people in the stories are doing now, at least for those who did not perish in future adventures—an occupational hazard.

There are no unsupported trips. In all cases, the parties were supported by food drops and friends and family for morale. The Ackerley brothers ate a few Canada geese (I don’t think they’re very tasty?) and Brando ‘Wildboy’ Yelavich ate rabbits, possums, black-backed gulls, goats, and pigs.

The parties also had different levels of experience before setting out on their trips. There aren’t any tales of underexperienced mountain parties (that doesn’t go well), but Brando set out on foot and obviously was highly inexperienced when he did, starting with a 60kg pack. He was presumably much more knowledgeable 600 days later.

There are no easy trips here. There aren’t any animals here that are going to kill you, but the climate and terrain are tough. It’s a bit of a self-fulfilling prophecy, of course, because an easy trip wouldn’t be that interesting to report on. But there’s always a part of each story about where the parties are at their breaking point (and some parts of some parties abandoned their trips).

Brando:

I completely broke. I threw my bag on the ground and sat down and started to cry. Then I started screaming, “Why am I doing this?” There was no one there to hear me or to answer my questions. I felt completely mentally broken … I just wanted a hug.

Travel was very much governed by the weather (and tide) conditions. Avalanches, storms, and waves are mightier than people, especially when using self-propelled means of transportation (but in all circumstances, really). Many of the trips involved a bunch of waiting for weather windows.

Reading through this, I reflected that I really have been to a lot of New Zealand places: I’d been to and recognized many of the places in the book, though I hadn’t always reached them by self-propelled means (e.g. Doubtful Sound, Mason Bay, Cape Reinga). I have some experience in most of the modes of transportation (though not caving), but certainly I haven’t tried to kayak around Fiordland, which has a reputation.

I also observed that in the earlier tales, navigation and communication were more of an issue, with broken radios and navigation by compass in kayaks. Wildboy, on the other hand, was doing it all on the Internet. Geoff Chapple, founder of the Te Aroroa, would have been one of the first to tramp with a laptop and post updates to his blog (since he was aiming to build public support for the trail).

The contents and voice are distinctly Kiwi; although the appendices enumerate traverses and circumnavigations including by foreign visitors, the stories that are told are those of locals. Like many New Zealanders, a number of the adventurers have spent significant time abroad. I don’t love the writing style: it has more clichés and adjectives than people usually use now. But this book is about the stories, not about their telling. I bet that in some cases the source material is a better read, though longer; Salisbury’s intent was to provide condensed versions of their stories.