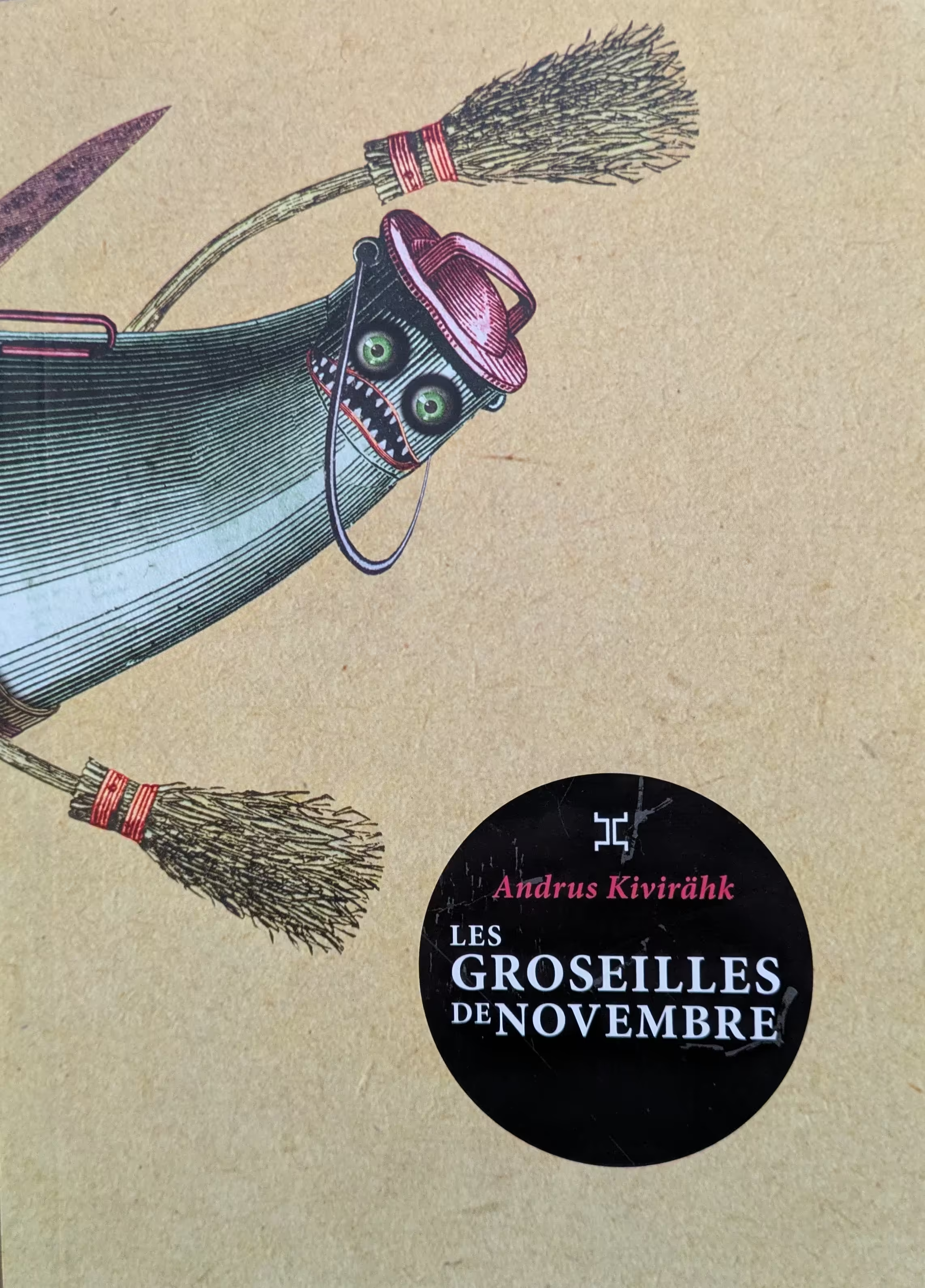

When I can, I like to read literature about places where I’m going. I had a week-long trip to Estonia to visit some collaborators so I asked about Estonian literature. Karoliine asked her friends for recommendations and got the response Les Groseilles de Novembre by Andrus Kivirähk. This book has not been translated to English but it has been translated into French, so I ordered it from Renaud-Bray in Québec and read it while I was in Estonia—too busy to read it before arriving.

Well, that was interesting.

There are no heroes. The characters in the book live in a small village in Estonia. As was the case historically, there was a German baron living in the manor, and the villagers were serfs (peasants? what’s the difference?) trying to live their lives. (Though the villagers did have houses. No talk of a housing crisis. The houses weren’t very good, though.)

In this book, almost none of the characters are, well, good people. Everyone steals food and trinkets from each other, and also the baron. Many of the characters have an extremely provincial view of the world; they usually haven’t left their village. The book is pretty much a Greek tragedy as I understand them; the author has no compunction about killing many of the characters throughout the book, and no one gets a happy ending (not even the Devil). People have unrequited crushes on other people, but there are no successful romances. There are funerals.

The villages’ worldview includes Christianity but also paganism. Indeed, pagan beliefs are very real in this village; as mentioned above, the Devil (also referred to as le Vieux-Païen, aka the Old Pagan) appears—at the crossroads—on demand and people try to trick him; transforming into a wolf on demand; and walking through walls. The devil also can facilitate the animation of kratts, sort of equivalent to golems. These kratts can steal stuff from neighbours and do household tasks, but will kill their owner if left idle. Apparently AI law in modern Estonia is called the kratt law.

The steward did make a kratt from snow, which told him (as well as the granger) stories that the water, animated in kratt form, learned from other places. The steward was one of the people who wasn’t a bad person, though a bit of a stalker.

The book is written in quite literary French, and there are quite a few words that I certainly don’t remember, if I ever knew them. Even Google Translate doesn’t know all the words. I didn’t really know, for instance, what a régisseur (steward) is. And there were a lot of words even more esoteric than that.

This book is a quick read, in that it’s pretty short, and has a short chapter for each day, but it’s not especially a light read, both in terms of gruesome subject matter, as well as challenging vocabulary, at least in the French.