Table Of Contents

Back for more. Again we’re talking about Emerald Hours in New Zealand by Alys Lowth, a travelogue about the author’s turn-of-the-20th-century travels in New Zealand as a tourist.

The table of distances and times. For the South Island it’s usually buses these days.

| distance (km) | 1906 | 2021 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Across the Cook Strait, Wellington-Picton | 92km | ⛴ 2pm–afternoon tea | ⛴ 3h20 |

| Picton-Nelson | (road) 139km |

⛴ overnight | 🚌 2h15 |

| Nelson-Motupiko | 57km | 🚆 2h | 🚌 1h |

| Nelson-Longford | 104km | 🐴🚃 0.75 days | 🚌 30m |

| Longford-Westport | 113km | 🐴🚃 1 day | 🚌 2hr |

| Westport-Inangahua Jct-Reefton | 82km | 🐴🚃 9h | n/a |

| Reefton-Greymouth | 77km | 🚆 3h | n/a |

| Greymouth-Hokitika | 37km | 🚆 1h | 🚌 40m |

| Hokitika-Greymouth-Kumara | 21km | ? | n/a |

| Kumara-Bealey Spur | 82km | 🐴🚃 1 day | n/a |

| Bealey Spur-Springfield | 72km | 🐴🚃 4-6h | 🚆 1.5h |

| Springfield-Christchurch | 63km | 🚆 3h | 🚆 1h |

| Christchurch-Lyttelton | 12km | 🚆 30m | 🚌 30m |

| Christchurch-Dunedin | 588km | 🚆 9.5h (min 6h) | 🚌 6h |

| Dunedin-Kingston | 270km | 🚆 5h? | n/a |

| Kingston-Queenstown | 40km | ⛴ 2.5h | 🚌 0.75h |

| Kingston-Lumsden | 60km | 🚆 2h? | n/a |

| Lumsden-Manapouri | 78km | 🐴🚃 7.5h | n/a |

| Te Anau Downs - Glade Wharf | 33km | ⛴ 3h | ⛴ 1h |

| Sandfly Point - Milford Wharf | 4.2km | 🚣 1.5h | ⛴ 20m |

| Te Anau - Dunedin | 287km | 14.5h | 🚌 2+4h |

Again over water

We’ll start this installment by talking about crossing a much smaller body of water than last time—straits, not oceans. The party took the Pateena from Wellington to Picton (one hour stop) and overnight to Nelson. These days, it’s easy to take the Interislander or Bluebridge ferry to Picton. The only transit link from Picton to Nelson is the InterCity bus. (From Picton you can also take the train to Christchurch on the Coastal Pacific). Or, you can fly from Wellington to Nelson, but we’re not talking about planes much here.

The boat will, of course, go through Queen Charlotte Sound, and it is still “beautiful” (also by airplane, which was not an option in 1906).

The 1906 dining experience on the overnight ferry was reported to be “a great deal better than any of the hotel dinners and infinitely better served”. The food on the Interislander doesn’t stand out. There is a Plus lounge on the ferry but I haven’t been to it.

And then there was talk of Pelorus Jack, a Risso’s dolphin that accompanied steamships between 1888 and 1912. It feels like the party got to experience firsthand a lot of what is in NZ lore: historic dolphins, hut construction on the Milford Track, meeting the guy after whom the falls are named…

Nelson to Westport

This took 2 days in 1905. The first day involved a train from Nelson to Motupiko (57km, 2 hours by train); just the next year, an extension to Tadmor would open (later than planned), and then in 1926 to Kawatiri, almost their full travel for the first day. The Nelson Section was an isolated railway line which ran until 1955. Stuff posted some history of the shutdown; like many misguided governments, the government of the time was after farebox recovery. Locals protested but only managed to briefly delay the shutdown.

Stagecoach to Longford

The next bit, getting to the West Coast (from where I’m currently writing this), was by stagecoach (8mph speed, I read elsewhere); there are still no quick connections to get to the still-isolated West Coast, Southern Alps being in the way. Another proposed way to the West Coast was the route of the Heaphy Track, but it’s good that they did not construct a highway there. Today, the ways to get to the West Coast are through Arthur’s Pass (car or train), Lewis Pass (car), or Haast Pass (car); or by flying to Hokitika.

The author mentions missing the views due to the clouds. Still a thing. No longer quite as much a thing: breaking a trace on a steep incline and trying to not freak out the horse. Still a thing: turns with recommended 15km/h speeds.

Speaking of inclines,

“[Coach driver] Newman pulled up, and asked the men on the coach if they would mind walking to save the horses, as we had come to a very steep hill,”

reminds me of something I’d read about the New Hampshire stagecoaches:

A sample fare schedule posted at Lincoln, New Hampshire:

- 1st class: $7.00 (rode all the way)

- 2nd class: had to walk at bad places on the road

- 3rd class: same as above, but also had to push at hills These NZ stagecoaches seemed to have been single-class, like Air New Zealand domestic flights today.

There’s also talk of seeing deer, wekas and rabbits. By that point stoats had been imported (since the 1870s) but I suppose there weren’t quite so many of them yet.

“make a stringent rule of always writing to engage rooms in advance, and as much in advance as possible”

This is now much easier with the Internet, although I have still made bloopers like booking two rooms for one night. But booking in advance doesn’t help with that, and indeed, it can contribute to it. Of course this has been the years of COVID when I’ve been travelling in New Zealand and rooms aren’t exactly full.

The author observes (gold) mining spoils on the landscape. We didn’t quite manage to see the press on the Paparoa Track because the bridge was closed, but there was certainly mining equipment left behind on the West Coast, as well as the infrastructure which preceded the trail.

Stagecoach to Westport

The party next continued to the West Coast, another all-day 113km trip along the path of today’s State Highway 6. However, it was not uncommon to have a single-lane road, which could be a hassle with horses: “we conjured up a vision of uncomfortable moments when we might have to back our frisky thoroughbreds for perhaps a quarter of a mile to let another coach, or a lumbering transport waggon, go by”. These days there are one-lane bridges, which do extend farther than 400m. Fortunately cars are fast.

“Like every other village in New Zealand [Lyell] swarmed with children”

No longer: NZ birthrate 1.61 births per women in 2020.

Along the way, the party reaches the Buller Gorge, which I’ve also passed through. For them, it was under mist. For us, well, I just don’t do that many water-based activities, so I haven’t stopped there.

Next up, in the book, there’s an illustration of gender stereotypes where the wife of Captain Greendays is the picky traveller who complains about subpar accommodation.

“And so, if you train him to strictly carry out the promise that coincides with ours to obey, he will unconsciously form a custom that will be at least a good working model of love and will obviate every mental reserve he may have made, and every arising difficulty, with regard to the bestowal of his worldly goods!”

says she. Feels dated to me in 2021 (but not completely inaccurate).

The party goes to a concert by Fanny Rose Porter, performing as Princess Te Rangi Pai, late in her career. NZ is small: I’m pretty sure I’ve read of her in museums here, and she is the author of allegedly famous lullaby Hine e Hine.

I have totally missed Westport so far, having proceeded directly to Charleston. They didn’t like it (“dingy dreariness”), after having spent two days on the “utter absence of comfort” on the coach being “cold and wet”.

Westport to Greymouth, and side-trip to Hokitika

They did not take the coastal road (now SH6), instead going back inland to Inangahua Junction and then presumably along today’s SH7 to Reefton, or else on the other side of the Grey through Blackball, then taking the train to Greymouth. I’ve driven Greymouth to Blackball for the Paparoa, but not Inangahua to Blackball.

As for Greymouth itself, I had a whitebait sandwich at Sevenpenny and thought it was good, while waiting for the return TranzAlpine. We stayed at a totally reasonable holiday park on another trip; the Australasian Bar & Restaurant was the only option, and it was fine, though not noteworthy. The author wrote about poor service and food in a Greymouth hotel, but we certainly didn’t experience that. The architecture is small-town NZ. Not bad. Their description: “[Greymouth] has therefore neither handsome houses with well-kept grounds nor a population that can afford to spend money on public gardens and an esplanade.”

Hokitika

Back then there was a train to Hokitika along the Ross (now Hokitika) Branch, running 2-3 times a day in 1906. These days there is still the train track, but the passenger trains stopped in 1972. Freight still runs daily.

They then proceeded to the races in Hokitika. I’m not sure what was racing. NZ still has a Racing Minister, which seems strange for 2021. There was talk about how all the women were dressed up, and of gambling recklessly in half-crown (inflation: $20) bets.

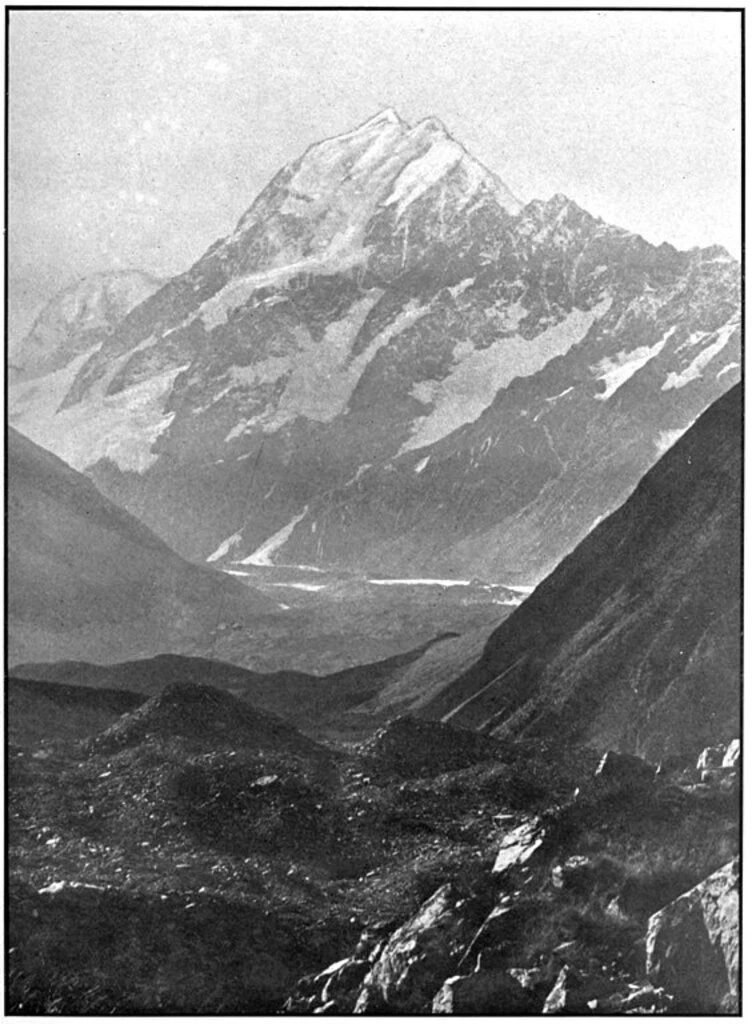

Hokitika has good views of the mountains, though Fox Glacier has better ones. Mrs Greendays was wise to seize her chance to see the mountain:

Mrs Greendays would not go down to the boat until she had made one of her “snapshot sketches,” in case the sky again clouded over before she had another chance.

Speaking of the boat, they then proceeded to Lake Mahinapua by oil launch (tide-dependent) plus toll bridge and enjoyed the reflection of Aoraki in the lake on a windless day.

They were also clever in making a last-minute call between Mahinapua and Kanieri depending on weather. I was hoping to see Aoraki and seized the chance to go early in the morning at Lake Matheson near Fox Glacier to see it after a day of grey skies and rain.

They also did a trip to Lake Kaniere (Kanieri in the book) and then went to take the train to Kumara.

Arthur’s Pass: Kumara to Otira to Springfield, train to Christchurch

At Kumara, they switched to the stagecoach again, even though the train did go all the way to Otira at this point. They mentioned that gold mining had already been relegated to being a thing of the past at that point, though coal continued until pretty recently. Coal mining can’t stop soon enough.

There was a stagecoach transfer at Otira (highly contended: not quite overbooked, but almost). Back then, Otira was “a very small settlement as yet” with “three or four houses, a school, two hotels, with the railway station”. These days the train still stops at Otira and there is also a pretty wild Otira Stagecoach Hotel (gallery). It’s still pretty small; Wikipedia puts its population at 651.

They crossed Arthur’s Pass overland. Cars still do that today on SH73, with a paravalanche these days entering the pass itself (I’m sure that didn’t exist in 1905! — just learned that it was built in the 1990s and provided shelter to a truck driver.). But since 1923, trains have taken the 8.5km Otira Tunnel. People say things take a long time now, but that tunnel was under construction from 1908 through 1918.

The day’s travels got them from Kumara over Arthur’s Pass to the Glacier Hotel, which I think was near the end of the Bealey Spur Track, 82km by my calculations, including passing over the Alps. The author said that the Glacier Hotel was the worst lodging she’d experienced to date.

We’d done Mount French to Arthur’s Pass recently and had a hiccup at Arthur’s Pass. That hiccup would have been impossible in 1905. Due to our hiccup, we got from Arthur’s Pass to Springfield in a tow truck; including the wait for the truck, it was probably comparable to their stagecoach time.

In Springfield, perhaps carrying on the legacy of the Glacier Hotel, there was a place (now defunct) which was notorious for bad service: “Springfield Store and Cafe: Come for the award-winning pies, stay for the abuse”. It’s now replaced by the “Taste of Kiwi” café. (I thought we weren’t supposed to eat kiwis).

Christchurch

The description of the Canterbury Plains is not too far off from today:

willows, Normandy poplars, and lime-trees to set them off, and even young oaks and elms now and then; there were fat white sheep and sleek dairy cattle in the pasture-lands, and an air of prosperity about it all.

The train, though, is now much more efficient (but much less frequent), and the author complains about long dwell-times at tiny stations in single-class trains. It took them 12 hours to travel the 139km from Bealey Spur to Christchurch, including 3 hours for the 64km from Springfield to Christchurch. Speaking of travel, passenger boats across New Zealand were still ubiquitous in 1906; planes weren’t a thing yet, and trains didn’t get everywhere—certainly not other parts of Australasia.

Christchurch was hosting the New Zealand International Exhibition at the time and they described the Canadian Court as being the place they were told to visit. Transit was via “electric cars” which I understand to be trams; on a Saturday night they were packed and “their warning bells going incessantly”. Crowded streets were due to the weekly “shop-parade”, i.e. Saturday at the mall for the shops that were open after dark in the summer (that’s not a thing now, stores are not open much beyond business hours). Not at all like Sundays in Zurich when everyone went for a walk because everything is closed. The exhibition was closed on Sunday, which would be less of a thing now.

Indeed, what are Sundays for? The author drops in comments about how they faithfully attend services on Sundays, possibly even more than one. And they write letters. Which does take a lot of time.

There was a comment about how one never appreciates one’s local tourist attractions; in London’s case, “Madame Tussaud’s and the Tower and National Gallery”, still true today, and in New Zealand’s case, Rotorua and the gorges.

They also visited Lyttelton by tram. The bus seems to take the same 30 minutes today as the tram did then. They did not have time to visit Akaroa, which would have taken a day and a half round-trip.

I don’t have a good sense of Christchurch from their visit as compared to immediately pre-2011 earthquake, but the author writes “And we came to the conclusion that if Christchurch does not so forcibly strike the English visitor as a familiar and home-like place as her inhabitants expect it is not the fault of her founders.”. My assessment is that especially the post-quake redevelopment is quite sprawling, unfortunately. It should be a great place for biking around, since it’s flat, but distances seem to be greater than they should be, separated by empty lots.

Their final activity in Christchurch was punting on the Avon, which is still a thing. Haven’t tried it myself though.

Christchurch to Dunedin

Christchurch is the end of the line for NZ passenger rail today (though I’ll write a note about Dunedin below). But until 2002 there was passenger service going further south: per Wikipedia,

“For much of New Zealand’s railway history, the passenger service from Christchurch to Dunedin was the flagship of the railway.”

At the time of writing, the trip took 9.5 hours; this got down to 5 hours 55 as technology advanced and stops reduced, which is the same time as the fastest InterCity bus (but trains are usually more comfortable than buses!)

The author notes plantings of now-disfavoured gorse, along with sycamores, limes, poplars, elms, and oaks. (Though the people running penguin conservation on the Banks Peninsula have used gorse to stabilize the landscape in preparation for subsequent naturalization; still, it’s prickly). She also mentions being home-sick for England. I’m not sure I miss Canada that much, really. And especially not during a pandemic.

Timaru, which I’d like to visit, had a “great future before it”. I think that future is still before it. They also passed through Oamaru, which is now famous for penguins and steampunk.

Dunedin to Queenstown via Kingston

We spent a few days in Dunedin at the end of 2020 (what else were we going to do around Christmas?) and, as the author says, Dunedin does have striking heritage architecture for New Zealand.

The public buildings of Dunedin are collectively finer than those of any other town in New Zealand, particularly the University and Boys’ High School. There are so many beautiful churches that it is difficult to particularise, but “First Church” is at least the most interesting, perhaps, and the Roman Catholic Cathedral the most imposing. Its climate is sharper in winter and not so warm and dry in summer as other parts of the Colony, but to counter-balance this it has the reputation of being the most hospitable, the most intellectual, the most artistic centre of all!

I only have pictures of the Knox Church in Dunedin, but yes, lots of churches, the Octagon, and many nods to Edinburgh. Climate? Well, I hear it’s extremely cold inside in Dunedin, even more so than in other parts of New Zealand (I’ve never heard of “warm and dry” being a thing that one has to look for in housing before coming to New Zealand).

Other fun facts about 2021 Dunedin: the airport is 30km from town (I saw someone setting up their bicycle for the trip) and you can see cows from the Koru Lounge.

More trains and boats

They then took a pretty slow train from Dunedin to Kingston (“a slender collection of cottages clustered round a station”, still the case today) and then the predecessor to the SS Earnslaw to Queenstown. Queenstown is much more accessible now by road and air, though I guess it’s never been accessible by rail. The Earnslaw is still running today, which is quite a long service life.

The foothills to the Remarkables visible on Lake Wakatipu before Queenstown didn’t impress them much, but the Remarkables did. Indeed, flying into Queenstown is super scenic and impressive. (Queenstown is kind of like Canmore in some ways.) Queenstown “seemed such a tiny hamlet”, which is still true on the world stage, but pretty big for NZ (population 16,000).

Queenstown

When they finally arrived in Queenstown, they were also impressed:

The sun was not shut out from Queenstown; the hills were not gaunt and grim and grey, but green and smiling, the houses white, the waters of the lake a lovely blue, and behind it all, reaching to the sky, there were dark, frowning peaks that accentuated the gracious scene they so jealously guarded.

They then went to the Shotover River, which is still famous, along Skippers Road, a feat of engineering that I have not yet visited. The attraction was gold mining. Now it’s rafting and jetboating. The dustiness is likely abated by being inside a car with closed windows these days.

FOMO then and now

The much-abused “Trots” are really greatly to be pitied. They arrive in a country on a visit, and are immediately presented with a list of places and tours quite disproportionate to the time at their disposal. They attempt to choose the best, but are invariably told as they proceed, and as their time relentlessly shortens, that those left out are by far the most important. And eventually, so anxious are they not to miss the chef d’oeuvre after coming so far, they try to see everything and end fagged out by rushing about, having had no real enjoyment of any one excursion, and carrying away only blurred and hazy recollections instead of one or two perfect pictures.

Some things never change. Even in 1905 people were still advocating for slow travel. The mystical before times never were.

Queenstown to Lumsden to Te Anau/Manapouri

Back on the launch from Queenstown to Kingston (2.5h), then train to Lumsden (back then departing mid-morning, arriving mid-afternoon?; later was the Kingston Flyer for which I could not find schedules). They had dinner at noon and high tea in the evening in the South in those days.

These days the thing is being stuck in an airport for hours, or overnight, in transit. Back then, they were stuck in Lumsden overnight and had to wait for the 10:30 buggy the next day. At least they weren’t sleeping on the floor.

Although New Zealand is full of serendipitous encounters, their friend the Man of Comfort (author’s appellation) turned up on purpose and saved them from the boring overnight in Lumsden. They then sewed up their own backpacks from old sailcloth and repacked. Gear was silk and wool, plus serge suits (I guess like the RCMP’s red serge?) The guide was to carry some more gear like extra boots and sheets.

Having packed, they then proceeded by coach from Lumsden to Manapouri. It took all day to cover the 78km, similar to up on the West Coast. Of course, now you can’t get from here to there on public transit anymore. After overnighting at Manapouri (still a couple of options today, including Kepler Mountain View Alpacas), they went boating on Lake Manapouri. These days you’d mostly do that to get to Doubtful Sound. Well, you take the boat and then the bus and then you’re on a boat on Doubtful Sound. I wish we had had time to overnight on that boat, it sounds great.

They then proceeded to Te Anau, 20km away, by coach. This was an evening’s ride. They were scoping out the others who were going to be on the Milford Track, as any humans will do. Without comment:

“We did not include our own party as we meant to avoid the others most scrupulously.”

“And we wondered what the solitary specimen of the stronger sex would do if the entire seven chose to faint at a crucial moment on the top of the pass?”

The Milford Track

Here we are at the climax of the book: the Milford Track, also known as “the finest walk in the world” (though that moniker probably came after the book). They were 10 days later in the season than us: mid-December for us, late December for them (we were on the Routeburn and around Dunedin in later December).

Day 1: onto the track

Their first day was pretty similar to ours. We also crossed Lake Te Anau in the rain. Back then, the boat ride was 3 hours and left in the morning (7AM) twice a week. Ours left at 2PM (and there is more than one boat a day) and took about an hour.

However, they stopped at Glade House, which is 15 minutes from the dock. There is still a building there with the same name today, used for guided trips, though probably it has been rebuilt. Like today, they enjoyed a meal prepared by the staff at Glade House. Meanwhile, they were second-guessing the other party, who said they were going to Mintaro (14 miles away, took us about 7 hours).

Day 2: to Mintaro

Their second day was Glade House to Mintaro (now a DOC Great Walks Hut), which they did quite a bit faster than us, given we had an hour’s head start on them, staying 5km in at Clinton Hut, and they had a long lunch. Their time was 6 hours, while ours was 7 hours, with a pretty short lunch break. We certainly did not get extra nails put into our boots. Maybe we watched weka:

wingless birds that are the most impudent birds in creation, with the magpie’s horrid habit of stealing and hiding anything bright.

Weka have impressive fast-twitch muscles! It doesn’t even have to be bright to get stolen. We successfully chased our lunch running away on Kapiti Island, as that weka had bitten off more than it could drag, but others lost chocolate to a weka on the Abel Tasman.

Certainly their supper was fancier than our dehydrated food, but not as fancy as the guided trips these days, who I think must get food in by helicopter for the farther lodges.

Dinner was ready by six,—hare soup, salmon, corned beef, potatoes and peas, apricots and rice, bread, biscuits, and butter, jam, cheese, and coffee.

Labour was cheap in that era both to bring in the food and to cook it; there were cooks stationed at the huts throughout the track. Not so today. The author also mentions that food cost 2/-, but I can’t translate that. Also, Mrs Greendays got a hot tub made up for her. We didn’t have that on this track. On the Hump Ridge Track, though, we did have showers included.

Day 3 part 1: over Mackinnon pass to the Sutherland Falls Hut

Late December snowstorm! It was a “grey and misty morning” but they decided to leave by 10am (we left Mintaro at 7:30am) and experienced “a biting wind” and a “perfect gale” with the snow. Sounds like Canada! We had great weather for Mackinnon pass, on the other hand, and got the views that they did not. The thing about Milford, though, is that you get the zillion falls if it rains, as a compensation for the missing views. We got them on day 4.

Mrs Greendays, the Captain’s wife in their party, is somewhat complainy on some occasions:

That she, the sedate, comfort-loving, highly-organised, carefully tended Englishwoman should be brought to such a place by her own husband, to be hustled and dragged, blown about and buffeted, in danger of her life at every step.

I’m surprised that their party walked faster than us. (This part of the day’s walk took us 6 hours without the snowstorm). Also, the guide was meanwhile reconstituting milk, which was a surprise to them. I would have thought that they would have seen powdered milk, for instance on the boat or something.

“What are we to say to the Admiral if Mary gets knocked up?”

Apparently knocked up means something different to them?

And, after getting milk and biscuits, Mrs Greendays complains:

“But my chief grievance is that we were not warned about the changeability of the weather!”

Changeable weather? Never happens in the UK!

Day 3 part 2: Sutherland Falls Hut to Milford Sound (!)

The others had decided to squat at the Sutherland Falls Hut, so the party could either kick them out, or continue to the end. (We’ve faced a full Atiwhakatu Hut and we just walked back out; not as much of an option on the Milford). The numbers don’t quite add up to me, or maybe the track has changed, but they allegedly had 19 miles left. My records show that the Quintin Lodge at Sutherland Falls is at 19mi, and total length is 33mi, leaving 14 miles.

In any case, either 14mi or 19mi is quite long for, say, a 3pm departure, even near the solstice. I’d count on at least 7 hours for 14 miles, which is pretty close to sunset at 9:30 (daylight time).

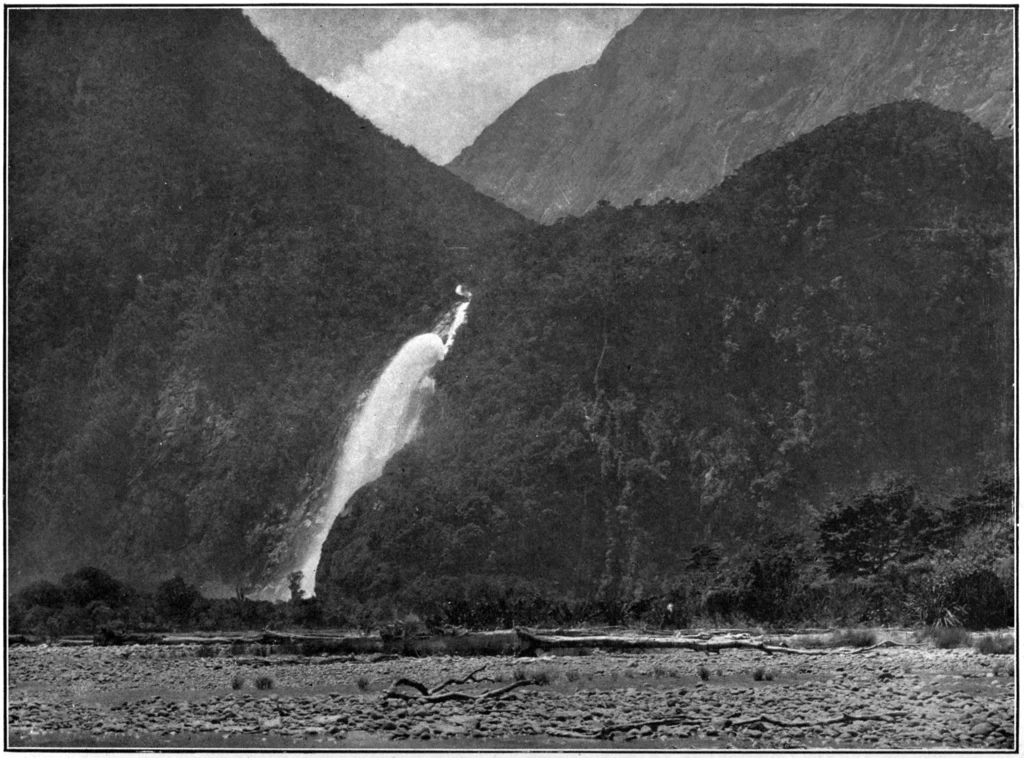

For us, Sutherland Falls was a sidetrip, adding about 1.5 hours. There’s no description of backtracking, but I also can’t see alternate routes on the map. Dunno.

To add extra drama, our heroine sprains her ankle. Which does happen to me after I walk for enough miles in a day, though it hasn’t happened in New Zealand for the past two years.

There’s mention of the suspended chair, which got replaced by a short-lived swingbridge in 1909, and then by a boat service. This is now at the Boatshed, where we got evacuated by helicopter due to over 100mm of expected rain later in the day, and newly-restored track after last year’s flooding. (We could have walked to Sandfly Point before the rain, given an early enough start, but I guess DOC didn’t want to chance it with all 40 walkers).

The party then rowed over Lake Ada, walked to Sandfly Point, and spent another 1.5 hours doing a night crossing of Milford Sound itself at Deepwater Basin (now a 20 minute boat ride).

Speaking of Sutherland Falls, they stayed at the accommodation run by Donald Sutherland (who did not answer the phone to retrieve them late at night) and his wife. “Hey, nice falls you’ve named after yourself!”

Milford Sound

They took a day of rest and puttered around the Sound (completely calm water) in Sutherland’s launch, not dissimilar to our August 2020 kayak tour which also had a local-minimum number of tourists.

They mock the other group, who had arrived later that day, for just getting to the Sound and leaving; of course, we spent only a rainy morning in Milford Sound on our trip, before taking the bus back to Te Anau. (We’d have liked to stay longer and take another, longer, kayak tour, but it’s currently super expensive to stay overnight in Milford Sound, as the backpackers doesn’t exist anymore).

The local Col Deane said that the Milford Track was in the process of being comfortized:

“In those days there was some spice of adventure attaching to an expedition over McKinnon’s Pass to Milford, but now they are fast making such a feather-bed thing of it that there will soon be no more novelty in the walk than there is to a Londoner in walking from the Marble Arch to Hyde Park Corner.”

These days, as we’ve established, the helicopter will rescue you if there’s too much rain; even the DOC huts are pretty flash (though they don’t cook for you); and the guided trip really does sound quite feather-bed.

While walking around the Sound near the top of Bowen Falls (which we haven’t gotten the chance to see yet) they saw dozens of green and brown parrots, presumably kakariki and kaka (kea less likely at Milford Sound), although they hadn’t seen any on the walk.

Return to Te Anau

Back then they couldn’t just get in a bus for the ride back, and there was no steamer around. So of course they had to walk back to Te Anau. They left at 6am, getting to Sutherland Falls at midday; DOC says that it’s about 7 hours, so, sure. Meanwhile, the NZ Tourist Department had put up two new huts in the few days since they had passed through (overtime pay for the workers). That’s how you avoid a housing crisis, although the huts might not be warm and dry.

They then left at 3 (long lunch!) and walked all the way to Pompolona, where the huts had been moved to. This time they got a clear day on McKinnon Pass. That all seems like quite a bit of walking to me: 8.5 hours. Should have taken them till 11pm. Go figure. They reckoned it at 30 miles, but my calculation also shows only 22mi (Pompolona is at 11mi and the end at 33mi).

The second day was a leisurely 11mi to the steamer to Te Anau.

Per Captain Greendays,

I really do call the scenery of this country top-hole, Deane, top-hole, no less! It has been a series of beautiful pictures all the way through, and by gad, old chap, we have a lot to thank you for, planning such a grand tour! The tourist department chaps looked quite flabbergasted when I went to them with your list of places the day we arrived in Auckland,—said it would be almost impossible to do it in the time, especially with two ladies,—ha—ha!

Te Anau to Dunedin

They had a long travel day from Te Anau to Dunedin (itinerary unreported) which took 14.5 hours. These days you can do it by bus, but it requires an overnight in Queenstown: 2 hours in the evening from Te Anau to Queenstown, an overnight, and then 4 hours from Queenstown to Dunedin.

Social engagements kept them busy on their weekend in Dunedin.

Dunedin to Bluff

After that, there was a train to Invercargill and then Bluff, involving another early morning departure. Bluff is on the Foveaux Strait and these days you can only get to [Stewart Island] from there, but I guess that back then they could take the boat to another continent.

“It is a pity that you could not have spent at least six months out here!” said Colonel Deane. “As it is you have only an impressionist idea of New Zealand to carry away with you. The best of the cities lies in their surroundings, which of course there has not been time to see, and then the places you have had to miss altogether! The Bay of Islands is a dream of loveliness, and the kauri forests up there are something entirely different to anything of the kind in the world. And Napier too,—I wish you could have seen Napier. It is such a pretty little town, and the district is one of the finest we have, with most undoubtedly the very best climate in the country. I don’t consider that anyone has seen New Zealand until they have been on a station at shearing time, inspected a milk-factory when the farmers were bringing their milk in, seen the gum-digging, and watched the kauri logs come down the great rivers.”

I’ve deinitely spent more than 6 months in NZ, and yet, I haven’t seen many of the places cited in that speech. I did see places where they used to run kauri logs down the rivers on Aotea though.

Summary

That’s quite a trip they had across the motu. There really was a lot of public transport capacity 115 years ago, a lot of which got replaced by (sometimes faster) buses. I’ve been fortunate to have visited almost all of the places that they got to, and I’ll plug my list once again.