Table Of Contents

Citation:

- André Brett (text) and Sam van der Weerden (maps). Can’t Get There From Here: New Zealand Passenger Rail Since 1920. Otago University Press, 2021.

Yesterday I was taking the plane from New Plymouth to Wellington. Google Maps says that this is 267km “as the kereru flies” (no crows in Aotearoa) or 361km by road. Door-to-door time was 3 hours with a shuttle on the New Plymouth side and transit on the Wellington side, so marginally faster than the 4.5 hours by car that Google Maps reports (and the 9 hours it took us on tourist time when we got a ride with in-laws).

As André Brett points out, cars are expensive, and New Zealand cities in the 1990s spent a high proportion of gross regional product on transport: 14–15.5% compared to a US average of 12.5% and Toronto 7.4%. In this case, we would have had to rent a car, and there are no rental cars. The InterCity bus was 7 hours and not daily; we probably didn’t even have time for it. So, for us, Air New Zealand it was.

History

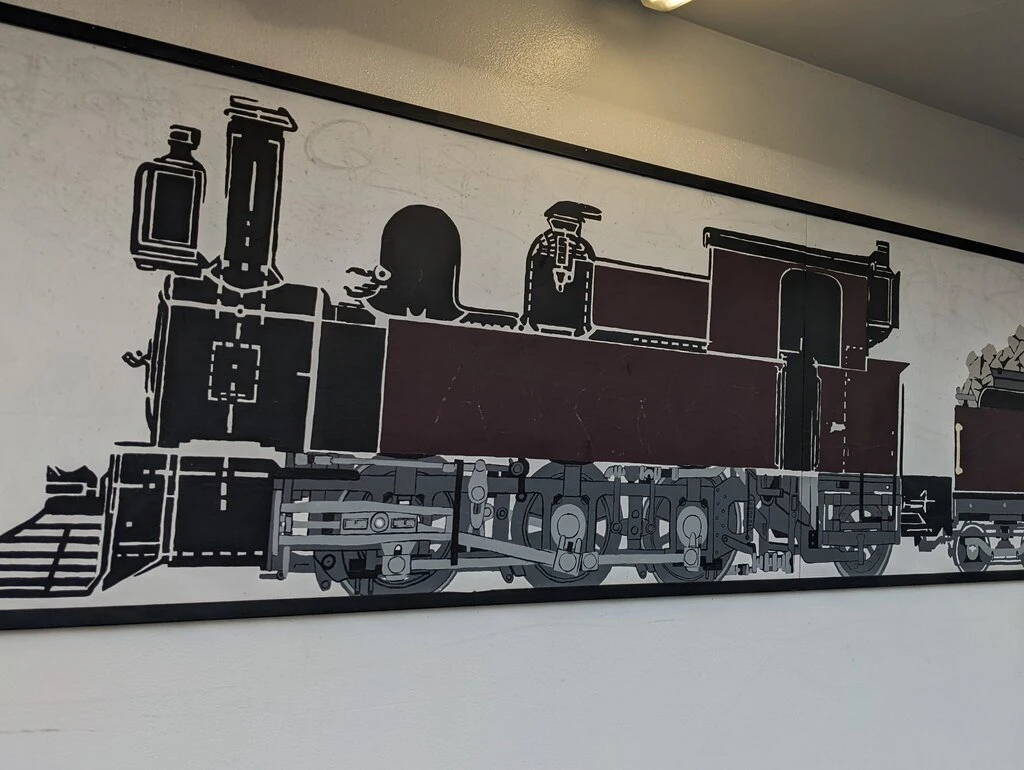

Can’t Get There From Here is about the sad history of passenger rail in New Zealand, but with the hope that we can build a better future informed by what has already existed. Pre-highways, there used to be a (geographically) extensive rail network, which the central government funded in service of the colonial project (“developmental”). Though it was extensive, passenger service to the periphery wasn’t fast, and was often inconveniently timed.

Last year, I was staying at the Holdsworth Lodge at the edge of the Tararuas, and there was a Lonely Planet guide from the turn of the century. NZ actually had much more passenger rail than today, as recently as 2001. But then the private rail operators shut it almost all down, except for three tourist lines across the country (Auckland-Wellington, Picton-Christchurch, and Christchurch-Greymouth), and a service from Wellington to Auckland.

Like in Los Angeles, buses were perceived as the hot new thing by NZ governments of the 50s. Indeed, for a while, rail and bus services were operated by the same organization, and government aimed to shift traffic to road, even when citizens expressed preference for trains. Los Angeles has been working hard to improve transit in the past few decades (though it’s hard). I hope New Zealand can also do that. (In the Waterloo ON context, I’ve spoken about light rail versus bus rapid transit.)

There is also a long tale of underinvestment in rail equipment across NZ governments of different parties. Some early Labour governments built more infrastructure than other governments, but no one managed to order locomotives and cars, and much equipment was substantial fractions of a century by the time it was decommissioned.

NZ Rail Services also didn’t really ever seem to work to improve ridership. Instead they would just observe low usage and, as a response, reduce schedules even more. There were few initiatives to actually promote rail.

The book documents in exhaustive detail the growth and sacking of the NZ passenger network, including its geographical extent, as well as the myriad failures to invest adequately in equipment and infrastructure, and the constant opposition by Treasury. Indeed, governments in Ontario and New Zealand in particular seem to be all about under-spending on critical public infrastructure (e.g. from another domain, Walkerton water quality, which caused a number of deaths; and yet the NZ media is fomenting great opposition to Three Waters, which is clearly necessary to avoid a Walkerton in NZ).

Rail Advocacy & Restoration

The last chapter of the book goes full advocate for passenger rail in NZ, laying out the case for a strong passenger network that would meet the needs of residents (and tourists). The vision is compelling. I hope we can get there from here!

Air New Zealand and other domestic airlines are making noises about zero-emissions aviation. They claim, and I more or less believe, that a full flight from Welington to Auckland consumes less gas than a two-occupant car (and certainly less than an ute with one person in it). But we have a climate crisis (it was shockingly humid—more than I’ve ever experienced in NZ—in New Plymouth) and that technology is not yet here. We can’t rely on it. It may not work out. Technology does that sometimes. We need to do the thing that is possible today.

Emissions aside (a possibility, I guess), the benefits of rail are (1) scalability and (2) intermediate stops. Canada does not experience (1) even on the Quebec-Windsor Canada; today, Air Canada, WestJet, and Porter provide way more capacity for Montreal-Toronto than VIA Rail does. VIA’s High Frequency Rail could get there, and it’s easier to add a bunch of cars than to buy more planes. For (2), New Zealand in particular had many towns on the Main Trunk Line in the North Island and similarly on the South Island between Christchurch and Dunedin. With good connections those towns could be more viable (I worry about sprawl; though maybe they still have enough infrastructure to not become bedroom communities).

It’s all about me

At the risk of engaging in elite projection: what trips would I personally do by rail and what trips by plane? I mean, sure, I can’t take the train to Christchurch (the Cook Strait is in the way), but I could certainly have taken it to Napier and New Plymouth—two of the places I went to in 2022, and both of which have been possible in the past, and proposed in Brett’s last chapter. Otaki Forks is just barely out of reach; I’d take the train to there and go tramping. The remaining regions of New Zealand that I haven’t visited—Taupo, the East Coast, and the Catlins—all could be served by trains, and I would at least take the train to Taupo and to Gisborne on the East Coast. From Wellington, I’d also go to the Taranaki region and National Park more (they have mountains!). Maybe Rotorua and Tauranga. I just don’t go to Auckland much and a train probably wouldn’t change that, and north of Auckland is really getting far from Wellington.

The rest of NZ

What about the populace and potential governments?

I browsed through some of the other submissions on the Parliamentary committee on inter-regional passenger rail (my submission). Consistent with Brett’s reporting in the book, there is broad support for rail among the populace, including for instance mountain clubs which would like another way of getting out there (it can be done in Switzerland!).

Brett mentions many New Zealanders returning from overseas—places with transit—and being told that this couldn’t work in New Zealand. He ably rebuts the arguments, in particular with a comparison to Norway (yes!). My question is how this happens: so many New Zealanders travel abroad, yet somehow the received wisdom swats them down when they get back to New Zealand. Like, I could believe it in the United States, but there are 1 million overseas New Zealanders. (The same argument applies to panic about inflation in New Zealand in 2022, which is indeed less than inflation in most other OECD countries, and yet).

Labour has done more than they get credit for but less than I’d like. There is an election coming up, and if National wins, I’m not optimistic about better rail; early in my stay in Wellington I noticed a prominent National MP running a petition in favour of a second Mount Victoria road tunnel (the bus doesn’t count? do you know about induced demand?).

Summary

André Brett’s work of scholarship, along with Sam van der Weerden’s maps, teach us about the past of the New Zealand passenger rail network, in great detail. Brett’s goal was also to investigate societal and institutional forces as well as the decisions that men made in overseeing the development and dismantling of New Zealand passenger rail. This is a history book, not a technology book, though it explains technical details as needed.

As a result of reading the book, I have a better understanding of how we got here from there. Perhaps most people wouldn’t read every word of the book and would prefer an executive summary, but, as an academic, I appreciate seeing the details.

Also by me on this topic

- Emerald Hours review (part 1, part 2): in which I appreciate a book describing a trip across New Zealand in the early 1900s; involves much rail

- My submission on inter-regional passenger rail: advocates for more trains

- In favour of LRT for Waterloo Region

Aside: regional English

“To grow custom” seems to have been written that way on purpose, but I don’t recognize it as Canadian or American English. NZ English is different! I guess it means “to grow the customer base”. I wonder which other Englishes it works in.